Great songs are where you find them. They can’t be confined to a single idiom like blues or folk. It’s the emotional, philosophical and yes, personal connection that makes it more than just words and melody expressed by the singer.

Bob Dylan loves songs—but, it seems he’s more passionate about contemplating the ones he didn’t write. He writes and records brilliant songs, but he seems to be as in awe of a song like “By the Time I Get to Phoenix” as you or I.

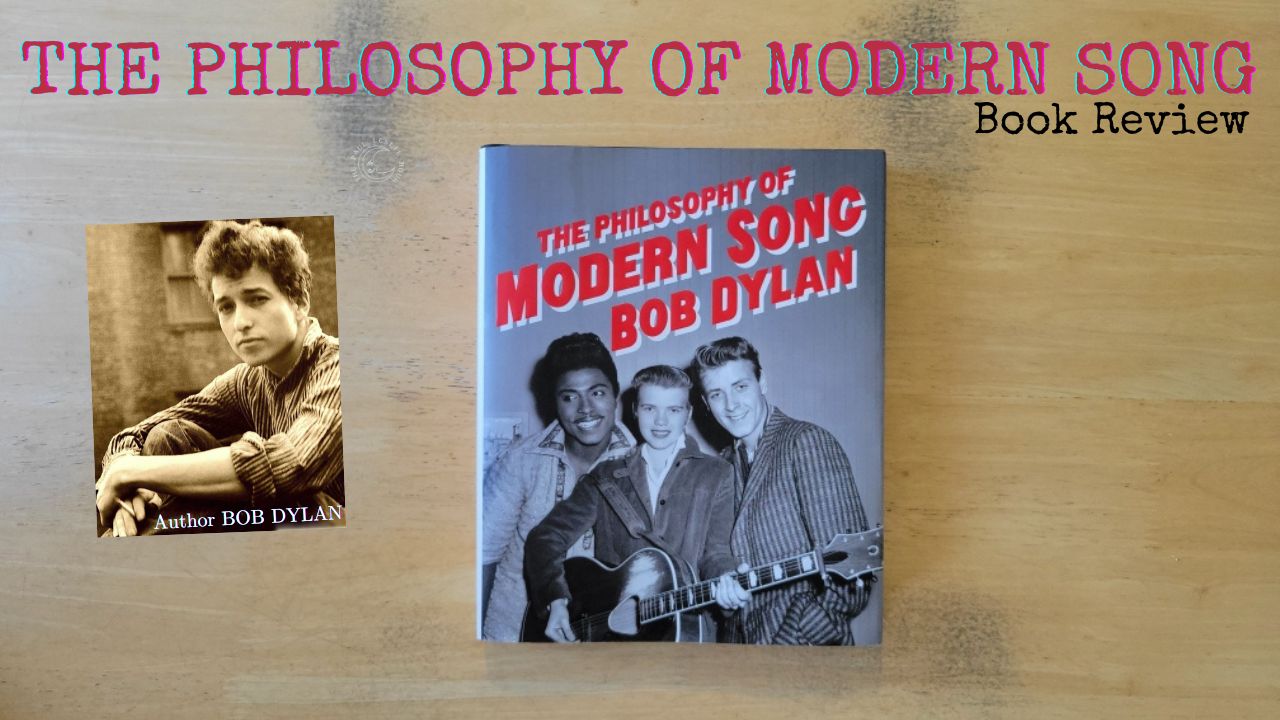

His new book The Philosophy of Modern Song, published by Simon & Schuster, is coming out on November 1, 2022. Dylan waxes philosophical about 60 songs, everything from rock and roll, country & western, and classics in the Great American Songbook. But never any of his own songs. Interesting, isn’t it?

It seems to be where he is at the moment. Consider that over the last 15 years he’s recorded twice as many tunes written by other songwriters as he has his material.

Chronicles: Volume One, which came out in 2004,was Bob Dylan’s last literary work. I’d been chomping at the bit for this latest book of his since news of its impending release. My heroes have always been songwriters, and to hear one of my favorite writers analyze song after song is just too good to pass up.

The tone of The Philosophy of Modern Song? Dylan writes as he speaks

Bob Dylan isn’t known for being the most loquacious song and dance man when he takes the stage. He lets his songs do the talking, but he’s compelling whenever he speaks.

Dylan’s quaint and at times folksy prose feels similar to his delivery on Theme Time Radio Hour that aired on satellite radio for 101 episodes. Eddie Gorodetsky, the co-creator, and writer of that radio show is given special thanks on the acknowledgment page.

Whether you think the “voice” of Bob Dylan is contrived or authentic, this book aligns with his diction.

The songs Dylan examines are exceptional

I knew most of these songs, written by quite an expanse of the best songwriters ever. Hank Williams. Jimmy Webb. Allen Toussaint. Harold Arlen. Johnny Mercer. The songs discussed in The Philosophy of Modern could be called modern in the sense that they were predominantly written in the 20th century. The songs that were released in the 1970s are the newer songs explored.

You may have noticed that “Nelly was a Lady,” written by Stephen Foster back in 1849, is the oldest song Dylan looked at. However, the recording Dylan references is the sublime Alvin Youngblood Hart interpretation from 2004. Newer songs just aren’t the name of the game here, but he venerates the tried and true songs from yesteryear.

It reminds me of Bob Dylan reading a listener’s letter on his Theme Time Radio Hour. The reader asked why he didn’t spin more new songs. Dylan responded: “The truth is there’s a lot more old songs than there are new songs.”

Many of the songs in the book have mesmerized me for years. I’ve found they have that quality that makes them more than just another song. The immediate titles that come to mind include “Beyond the Sea,” “A Certain Girl,” and “Detroit City.” But then there’s “My Prayer,” and I can’t leave out “On the Road Again.”

There’s a certain everyman appeal to the songs and the way Dylan shines a light on them. It’s as if you bumped into him at some late-night diner, and he’s reflecting on the song he picked from the jukebox. He’s breaking the song down as much for himself as for you.

The Philosophy of Modern Song is a beautiful hardcover book

Before you read a word of this book, it’s the visual aspects that draw you in. Throughout 352 pages, the reader is treated to a smorgasbord of color and black-and-white photography.

One of the most impressive things about The Philosophy of Modern Song is the great care put into the design. Aesthetically the book is reminiscent of the late Harris Lewine. That’s a good thing.

The Philosophy of Modern Song was designed by Coco Shinomiya, a Grammy-nominated graphic designer. It’s decidedly retro.

You’d expect to see album art, but you’ll also find artwork, old lithographs, and old magazine advertisements, all woven between art deco borders. There were lots of archival photos I’d never seen before. The page layout is visually tempting.

“Play me a song,” to quote Dylan’s lyric

I find myself thinking about what makes a great song a great song. We can almost all agree that “I’ll Fly Away” is an exceptional song, but why?

What is it about the nature of songs that makes them so regenerative? We seldom reread a book, but there are songs like “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” that I’ve never remotely tired of.

I found myself contemplating this on more than one sleepless night. Thinking about The Philosophy of Modern Song sparked a memory of hearing Bob Dylan’s song “Murder Most Foul” for the first time in 2020. Throughout the almost 17-minute-long song, Dylan names more than 70 songs, always requesting or commanding the listener to “play another one.”

Therein lies the one obstacle I had while reading The Philosophy of Modern Song. Over and over, I had the impulse to hear that song, right then and there. Sometimes it was because of the curiosity of having never heard a song before.

Other times it was because the writing made me see a certain song in an entirely different way, like Bobby Darin’s “Mack the Knife” or Billy Joe Shaver’s “Willy the Wandering Gypsy and Me.” I had to listen to the song one more time. Right then. Right there.

Songs were always important to Bob Dylan, but they may matter more to him now than ever.

The Philosophy of Modern Song is available on November 1, 2022. It’s available as a hardcover, Kindle, audiobook and on CD.

If you get your copy, please reach out and give me your thoughts.

Thanks for the review. I’m reading about one song a day and listening to it on YouTube…or wherever I can find it. I don’t want to read through this volume quickly. As always, Dylan is pointing his listeners and readers to other artists. He’s a master teacher.