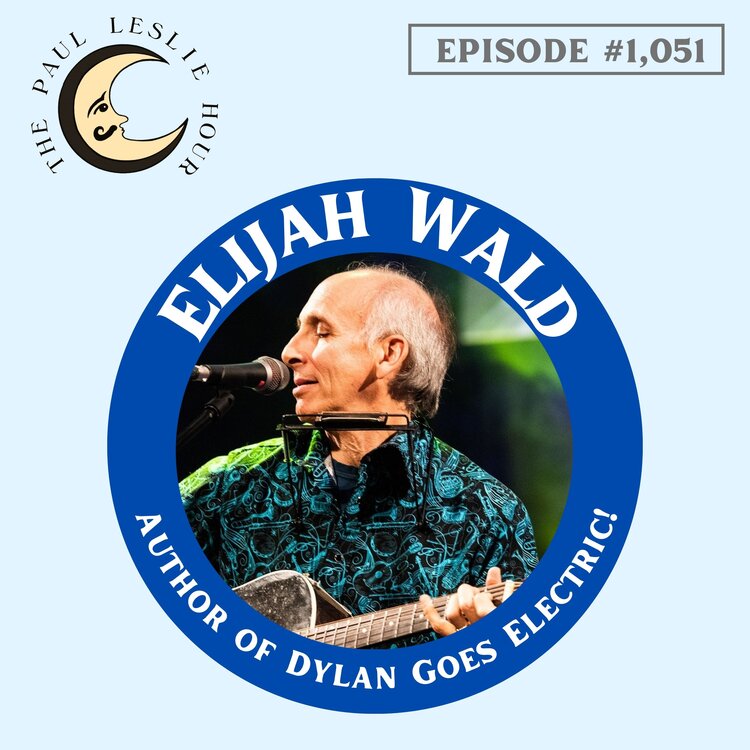

Elijah Wald joins The Paul Leslie Hour!

Are you here?

We’ll answer that question for you. You’re here, tuned into The Paul Leslie Hour, episode number 1,051.

We’re pleased to present an interview with Elijah Wald, author of DYLAN GOES ELECTRIC! Newport, Seeger, Dylan and the Night that Split the Sixties, which inspired the major motion picture A Complete Unknown.

Please keep in mind folks, The Paul Leslie Hour is made possible by viewers and listeners like you, please go to the supporter’s page and we thank you for listening and supporting!

And with that, what do you say we start the first interview of 2025?

Help Support the Show Here

• Apple • Spotify • Audible • iHeartRadio •

Elijah Wald: Interview on Dylan Goes Electric!

Official Transcript

Well, ladies and gentlemen, it’s my great pleasure to present an interview with Elijah Wald, a writer, musician, journalist, music historian, and New York Times bestselling author. Wald is the author of Dylan Goes Electric: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the 60s, which inspired the movie A Complete Unknown.

So, Mr. Wald, how are you doing?

ELIJAH WALD: I’m doing fine. It’s been kind of a wild month.

I bet. I bet. It must be exciting, too.

Yeah, no, it’s been fun. I mean, you know, the most exciting thing was that tweet from Dylan that he liked my book, which I had no idea that he had himself read it. I knew that his people had licensed it, had optioned it for the movie. But discovering that he had read it himself and liked it was exciting.

I bet.

And unexpected.

What inspired Elijah Wald to write Dylan Goes Electric!?

What made you feel that this specific story needed to be told, the story told in Dylan Goes Electric?

I’m not going to say “needed to be told.” I’m a professional freelance writer. What struck me was that the 50th anniversary was coming up, and if I wrote the book on Dylan going electric, I could get a good advance and sell a bunch of books.

I mean, this one really started as a commercial prospect. As it turned out, I then got utterly fascinated with it, and I’m very pleased with the result.

But when the original idea…Was that it was going to be quick and easy to write because there was already so much available on the subject. As it turned out, I ended up with a very different slant than what was already available on the subject, and it was the hardest work I’ve ever done in my life.

The difficulty of writing Dylan Goes Electric!

What about it would you say made it such hard work to write this one?

Frankly, I had the idea late and had to do all the research and writing in six months. On the other hand, I think in the end, that made it a better book because it reads quickly. I mean, I hope people agree that it reads quickly as well as having been written quickly.

I think it gave it an energy it wouldn’t have had if I’d had infinite time to do research and writing.

I can see that. I read the book very quickly, and I love the way that it balances being storytelling in that it feels very much like, “Oh, this is a story.”

I can actually see how somebody would read the book and think, “This would be a good movie.”

It sure didn’t occur to me, but I’m glad they did.

Dylan Goes Electric! – just the facts, please

How important was getting to the truth a part of writing your book, Dylan Goes Electric?

Okay, I’m going to make one of those subtle distinctions. Getting to the facts as much as possible was important. The truth is a much trickier question.

And to me, the truth I was trying to get to was how complicated it was. I mean, my dream writing the book and still my dream about the book is that people who go in thinking they know how they would have reacted when Dylan went electric at Newport… my dream is that by the time they reach that point in the book, they not be sure how they would have felt about it. I wanted people to feel more, more torn by that moment.

Then, you know, I think everybody going in thinks, “God, how stupid to boo Dylan for going electric.” And I wanted to make it more complicated than that. Because, I mean, that is the truth. To me, that is the truth of that moment, that it was a complicated moment, not the simple story of the boring old folkies didn’t appreciate the genius.

Dylan’s team gets involved

How did you find that the book was going to be made into a movie? How did that all happen?

Dylan’s people, they were the ones who originally optioned it. I got a phone call from his manager saying they wanted to option the book.

What did you find them to be like, to deal with, the Dylan folks?

Well, Dylan’s manager is very easy to deal with, as long as you don’t want to talk to Dylan, and I didn’t.

That’s interesting.

They were incredibly helpful. As soon as they found out I didn’t want to talk to Dylan, they were prepared to do anything. You know, they were extremely helpful.

And as for not talking to Dylan, just in case people are perplexed by that.Dylan has been interviewed infinitely about that period. If there’s one subject he never needs to be questioned about again, it’s that. And what I wanted was to find what his reactions were closer to that time, not how he had by now reshaped it in his mind 50 years later.

“I’m not interested in interviewing him”

So you let them know immediately, “Look, I am not seeking any sort of interview with Bob Dylan.”

Yeah.

Smart. Now, that said, if you could ask Mr. Dylan anything, what would you ask him?

Oh, hell, I don’t know. No, I mean, honestly, I mean, I would be interested to meet Dylan, but I’m not interested in interviewing him.

Right.

We have friends in common. And what they have said to me is, if you met Dylan, what he’d want to do is talk about old pre-war blues guys. I mean, honestly, I was surprised he had read this book. I assume he’s read my Robert Johnson book. That’s what interests him.

Wald’s thoughts on the A Complete Unknown movie

What did you think of the movie when you saw it the first time?

I liked it.

I mean, you know, it’s large. They’ve invented an awful lot of scenes. They’ve invented, you know, virtually all the scenes. But within that, I was astonished by how much they got right and also really pleased with just how much music is in it and how well the music is done.

Not just Dylan’s music, but I was actually infinitely relieved at how well they handled Pete Seeger and Pete Seeger’s playing. And Monica Barbaro’s Baez, I also thought, was very impressive. I mean, the music throughout was just treated so well. And for me, that was the most important thing. But secondarily, they got so many details right. There’s some little things that annoyed me, but so little that they don’t count.

I have to agree with you on the music. The music, it just, you know, it’s a cliche, I guess, but the songs come alive.

Yeah, no, I mean, they give the songs context. I was there with someone who was not as familiar with them and who came out much more excited about Dylan’s songwriting than she went in. And, I mean, that’s, to me, that’s what the film’s for. But again,

I also thought the fact, you know, they got so much right, so many little details. I’ve now seen it three times. And each time I picked up things I had missed before, just little things that they put in for the Dylan nuts. And my experience, you know, I’m seeing a lot of reactions, is that mostly the people who were actually around on that scene are just loving the film because, you know, they’re reliving their youth. Which is nice.

Bob Dylan and social media

You mentioned that you were surprised when you read the tweet from Bob Dylan where he plugged both the movie, but he also made sure to tell people, after you see the movie, go read the book.

Well, I mean, that was just a plug. What I loved was him referring to the book as fantastic.

Yeah.

But yeah, I was astonished.

What do you make of him tweeting in the first place?

I haven’t—who knows? I mean, that Bob Dylan should get engaged with social media—you know, it doesn’t… I didn’t expect it. It didn’t surprise me. I don’t know the man, and the man—you know, Bob Dylan has been surprising us for as long as I’ve been aware of him and longer. That he should surprise me again, you know, it surprised him tweeting surprised me less than him recording a Sinatra album.

What did you think of that?

I wasn’t wild about the album. When I saw him live after that, I actually liked the standards more than I liked his versions of his own songs. He did it with a much more stripped-down band, and I could hear him more clearly, and I thought he did them beautifully. I don’t need the record, but then I’m not a Sinatra fan either.

Pete Seeger’s legacy

Well, Pete Seeger is, of course, an integral part of your book. He’s someone who’s perhaps more complicated than he seems on the surface. How would you describe the late Pete Seeger?

Like you say, he’s more complicated than he seems on the surface. I spent a lot of the book—a lot of people came away from that book saying that they didn’t learn so much about Dylan, but they learned a lot about Seeger. And I think a lot of people are coming away from the movie more surprised with how Seeger shows up than how Dylan shows up.

I mean, he was what people meant by folk music by 1960, was the stuff Pete Seeger plays.

And even the people who completely disagreed about folk music all meant the stuff Pete Seeger plays because there was no element of the folk scene that didn’t come directly out of Seeger.

I mean, he had been one of the leading figures in the first wave of folk protest music with the Almanac Singers. With the Weavers, he invented the pop folk style that was carried on by the Kingston Trio and Peter, Paul and Mary.

And in 1950, he made an album called Darling Corey, which was the first attempt by a middle-class urban musician to replicate traditional southern banjo styles as they were played by the original players, leading into people like the New Lost City Ramblers and Dave Van Ronk. I mean, every element of the folk scene came out of Seeger.

Did Pete Seeger get the recognition he deserved?

Do you think Seeger has gotten his due?

No, but I should add to that.

It’s kind of impossible for Seeger to get his due because unlike Dylan, whose records I think capture what was great about Dylan, Seeger’s records give no hint of what was great about Seeger. If you didn’t see him live, you don’t understand what the thing was that he did.

I mean, I can say it, you know, we can all describe it. But Seeger was magic on stage, and that’s what he did.

The other thing is, you know, Seeger had no interest in us remembering Seeger. Seeger wanted to leave behind a completely different—he would have liked to leave a completely different, not just musical world, but world in general, but certainly a different musical world. But he always felt like his job was getting everybody else who he thought was important up front and getting people singing together. And his view was always, “I’m just one of the many.”

So, you know, the fact that he is not personally remembered as much of a giant as he was would not, I think, surprise or disappoint him.

And the fact is, you know, most people—I don’t know about most people, but his name is still well known. I mean, Bruce Springsteen has done a Seeger tribute album. He’s prominent in this movie. It’s not like he’s disappeared.

Right.

People who were very close to Pete Seeger never felt they understood him. I think the difference between Bob Dylan and Pete Seeger is not that Dylan was a more complicated and in some ways difficult person to know. It’s that everybody knows that about Dylan. Whereas if you saw Pete Seeger live, you felt like you knew him. You were wrong.

I mean, one of the funny things about Pete Seeger, and people have said this over and over and over, is if you saw him live, you felt this incredible warmth and closeness. And if you actually were one-on-one with him in a room, he was much more distant and harder to know.

That’s so interesting. Yeah, when I interviewed Seeger, I thought that there would be this kind of—yeah, I thought that I would get the image of the guy.

We’re talking about Seeger here, and you mentioned Dave Van Ronk earlier. There are so many of these other folk artists that you encounter in your book. People mention Joan Baez, Peter, Paul, and Mary, some of these others. Why do you think they didn’t get the fame and recognition of Dylan?

Look, Dave’s answer would be very simple. I mean, Van Ronk always said, the minute Dylan came on the scene, it was obvious to him that Dylan was something different and that Dylan was just vastly more talented than the rest of them.

I know there are plenty of defenders of Dave who will deny that. And God knows defenders of Phil Ochs will deny that. But I think that’s the simple answer. The slightly more complicated answer is that one can disagree about whether Dylan was more talented, but the fact that his talents dovetailed with the moment and the Rolling Stones and what was happening in popular music is undeniable.

Dave Van Ronk

You wrote a book with Dave Van Ronk. I’m hoping you can give us a little snapshot. What was the man like?

First thing to be said is, he dropped out of school when he was 12 years old, and he was the best-educated and most intelligent human being I have ever met in my life. And I thought when I got deeper into academia, I might meet somebody who was as broadly knowledgeable as Dave Van Ronk. I never have.

He was also an incredibly funny man. Yeah. I wrote one book with Dave Van Ronk, but all of my books exist because of what I learned from Dave Van Ronk, not as a musician, but as a scholar and somebody deeply knowledgeable about writing and about good writing. I mean, when I became a newspaper writer, Dave loaded me down with books, saying, if you’re going to do this, these are the people you need to read—A.J. Liebling, principally. He would have liked me to get deeper into Mencken, which didn’t work for me.

He was the first person I ever heard make just sort of offhanded criticism of Shakespeare. It hadn’t occurred to me that you could criticize Shakespeare. And Dave just sort of in passing said, “you know, the problem with Shakespeare was he wrote so beautifully that when he ran out of things to say, he didn’t stop.”

It’s not a—I mean, I think that’s, obviously there’s plenty more that could be said on that subject, but I think also it’s obviously right. And as I say, what was breathtaking for me was it had never occurred to me that ordinary people like us who hadn’t been to college would even consider having an opinion about, would consider saying a sentence that began with “what’s wrong with Shakespeare as a writer.”

“The main thing I’m working on is a biography”

Very interesting. So what is on the horizon with Elijah Wald? What are you working on these days?

Oh, a bunch of things. I’m finishing up a short history of rock and roll for Oxford University Press’ Very Short Introduction series. I’m doing an anthology—trying to find a publisher for an anthology of writing by a man named Robert McKinney, who was the one Black writer with the New Orleans Federal Writers Project during the Depression era.

The main thing I’m working on is a biography. My last book was a book on Jelly Roll Morton and hidden stories and censorship of early blues. And in the middle of that project, he mentioned just in passing a woman named Reddy Money, who was the most expert pickpocket in New Orleans in the first decade of the 20th century. And I just thought I’d look her up. And anyway, I’m now doing a full-scale biography of her.

As it turned out, she went from being a pickpocket and sex worker in the 1880s and 90s to owning the largest Black-owned hotel in Southern California. It’s an incredible story. And nobody’s written a paragraph about her. She’s completely unknown. So that’s what I’m doing now.

How interesting. Wow.

“I’d like them to walk out of it less sure of how they feel about that moment”

For anyone who reads your book Dylan Goes Electric! or sees the movie A Complete Unknown, is there anything that you’d like for them to get from that experience in specific?

Like I said earlier, just, I’d like them to walk out of it less sure of how they feel about that moment. I mean, you know, most people in that moment were confused by what was going on. You know, something is happening there, but you don’t know what it is. Do you, Mr. Jones? I think, you know, how does it feel? Most people were like, well, I’m not sure right now. I need to think about this a minute.

I want —I was trying to give people a sense of the period, and I was trying to give them a sense that Pete Seeger’s position when he was upset by what Dylan was doing was just as valid as Dylan’s position. And, you know, I think it’s worth remembering that both of them continue to honor the other and the other’s position.

The history of that period was originally written by rock fans who were not particularly interested in folk music. By now, I think everybody who’s into Dylan thinks of him as sort of the patron saint of what’s now called Americana, of people who were absolutely immersed in old blues, old country, old, you know, old music.

Nobody thinks of Dylan anymore as the guy who rejected old music to do something modern. He has been the—he’s been keeping the flame of devotion to American roots music alive. And that’s how pretty much everyone, I think, now thinks of him.

Well, Mr. Wald, thank you so much for coming on here and talking with me. And congratulations on the movie and for writing such a compelling book.

Thank you.

Thank you so much!

Okay

Have a great one.

You too.